| Home » » Swami瑜伽性侵大師 |

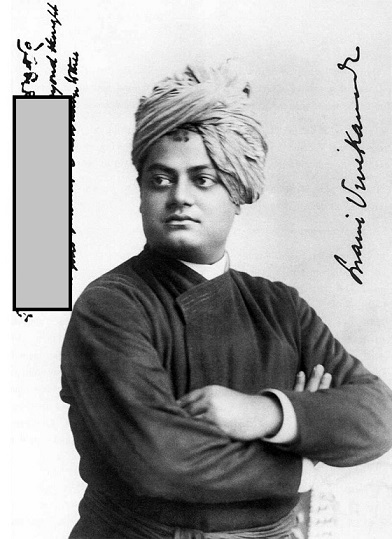

Swami Vivekananda——帥氣的鴨子 |

維韋卡南達(Swami Vivekananda ),1863年1月12日——1902年7月4日,原名Narendranath Datta,印度神秘主義者羅摩克里希納的首席弟子。18歲時,他遇到了Ramakrishna,後來成為其忠實的追隨者(男寵)。1893年,前往美國參加芝加哥宗教議會,發表演講一炮而紅。之後在美國、英國和歐洲發表了數百場演講,傳播印度教哲學的核心教義,是印度教吠檀多向西方世界最成功的傳教士。 維韋卡南達不僅被視為印度復興的愛國先知,也被視為濕婆、佛陀和耶穌的化身(Sil,1997)。(版按:哇!好神奇!教義完全相反的各個教派的教主都融合了、貫通了,全部匯集到他一身。後面還聲稱自己是印度教改革家——商羯羅的轉世。就他的知識面,如果擴大了而知道中國還有位道家的老子、儒家孔子,不知道二位名號是否夠響亮、能夠入得他的眼?人說萬千寵愛集一身,他是萬千化身為一體!) 維韋卡南達從出生起就是完美的,他不需要精神紀律來獲得自己的解放。無論他實行什麼戒律,都是為了暫時揭開掩蓋他真正的神性和在世上的使命的面紗。甚至在他出生之前,主就選擇了他作為幫助他進行人類精神救贖的工具(Nikhilananda,1996)。

《《他認為自己是個禁慾者,一個印度教傳統的獨身學生,他努力工作,珍惜禁慾紀律,崇敬神聖的事物,並享受乾淨的言語、思想和行為(Nikhilananda,1996)。》》 他是一位英俊、肌肉發達的年輕人,儘管有些粗壯,下巴像鬥牛犬一樣,1881 年,18歲的他第一次見到了他的導師羅摩克里希納。身為「至尊天鵝」最愛、最重要的弟子,年輕的「小鴨子」維韋卡南達, 《《他不斷地受到他坦率的、著迷的同性戀導師——羅摩克里希納的奉承和寵愛,被他崇拜地餵養,為了大師的神秘歡樂而定期唱歌,並被年長的男人告訴他. .....透過冥想實現了個人…[一個]永恆實現的人…擺脫了…女人和財富的誘惑(Sil,1997)。》》 1886年,即他的古魯去世前不久,維韋卡南達吉 (Vivekanandaji) 發誓成為一名出家者。(在東印度名字和頭銜中添加後綴“ji”以表示尊重。)“Swami”本身——意思是“成為自我的主人”——只是商羯羅在十三世紀建立的寺院名稱。採用此尊稱需要正式宣誓獨身和貧窮。 有趣的是,在後來的幾年裡,維韋卡南達實際上聲稱自己是商羯羅的轉世(Sil,1997)。(版按:轉世輪回是法界的真實狀況,不幸的是,這也成爲宗教騙子欺騙信徒的絕佳工具,反正信徒們也沒有宿命通,如西藏密宗的活佛轉世一樣,就盡量理直氣壯、放心大膽地吹噓便是。) 無論如何,經過十幾年對他已故的上師日益虔誠的奉獻,維韋卡南達在三十歲時來到了美國。 1893年,他在芝加哥舉行的宗教議會上向美國男女代表印度教。 《《他對外向、受過教育、富裕的女性世界完全陌生,卻被她們的慷慨、善良以及對來自遙遠國度的英俊、年輕、機智、有點迷人天真的處男的坦率無條件的欽佩和痴迷所迷住。西爾,1997)。》》 然而,乍一看,羅摩克里希納向維韋卡南達保證的自净會帶來純潔和享受,以及“免受女性誘惑的自由”似乎有些不完整。因為,維韋卡南達曾承認,1884 年他父親過世後, 《《他在朋友的陪伴下參觀妓院並飲用酒精飲料(Sil,1997)。》》 不過,值得慶幸的是,維韋卡南達並沒有真正享受這些房子裡各種女士們的快樂。相反,根據他自己的證詞,他只是被他的朋友拖到那裡,希望在他父親去世後讓他振作起來。然而,喝了幾杯酒後,他開始向他們說教,告訴他們這種放蕩的行為在來世可能會發生什麼事。隨後,他因「不識相、掃興」而被朋友們趕了出來,然後獨自跌跌撞撞地回家,喝得酩酊大醉(Sil,2004)。 所以只是喝了幾杯太多了。妓院裡。救世主「被上帝選為幫助祂的工具」來拯救人類,這並不令人意外。 《《我心中立刻升起了慾望的感覺。我對自己感到非常厭惡,以至於我坐在一盆燃燒的火絨上,傷口花了很長時間才癒合(《Sil》,1997)。》》 ** ** 宣布這一消息後不久,維韋卡南達就自豪地聲稱自己「幫助應對了席捲世界的吠檀多浪潮」。他同樣很快就預測「十年後,絕大多數英國人將成為吠檀多派」(Sil,1997)。 此外,這位熱情的年輕僧侶希望實現全球變革,並不僅限於「世界各地的印度教徒」的精神革命。相反,他的其他宏偉夢想包括建立一個社會進步、經濟主權和政治穩定的印度(Sil,1997)。 然而,要實現這些目標,就必須面對某些出乎斯瓦米意料之外的具體現實,包括在表達自己的想法時需要事先思考。事實上,維韋卡南達似乎明確反對這種做法: 《《計劃!計劃!這就是為什麼你們西方人永遠不能創造宗教!如果你們當中有人這樣做過,那也只是少數天主教聖徒沒有計劃。規劃者從來沒有宣揚過宗教! (尼基拉南達,1996 年)。》》 因此,考慮到這種反感,維韋卡南達在 1897 年底之前就已經縮小了他的目標,也就不足為奇了: 《《我已經喚醒了我們很多人,這就是我想要的(Nikhilananda,1996)。》》 此外,正如 Chelishev (1987) 在談到天真的僧侶所倡導的社會進步時所觀察到的: 《《維韋卡南達從空想社會主義的立場來解決社會不平等問題,寄望有產階級的善意與寬容。》》 可以理解的是,一年之內,斯瓦米就意識到這種方法是徒勞無功的: 《《我目前已經放棄了對群眾進行教育的計劃(Sil,1997)。》》 《《它會逐漸到來。我現在想要的是一群熱情的傳道者。我們必須在馬德拉斯有一所學院來教導比較宗教……我們必須有一家出版社,以及用英語和白話文印刷的論文(Vivekananda,1947)。》》 《《斯瓦米有很多好主意,但他什麼也沒付諸實行……他只是說說而已(《Sil》,1997)。》》 ** ** 這位連續吸煙、患有糖尿病的聖人,表面上“溫柔地走進那個漆黑的夜晚”,然而幾年後,也就是 1902 年,在健康狀況逐年下降之後,他就去世了。他年僅三十九歲,「就這樣實現了他自己的預言:『我活不過四十歲』」(Nikhilananda,1996)。 當然,有預言,還有更早的預言: 《《維韋卡南達莊嚴地宣稱:「這次我會活到一百嵗……這次我要完成許多艱鉅的任務……這一生我將比前世展示更多的力量。」(西爾,1997 )。(版按:這位維韋卡南達,一會兒說自己活不過四十嵗,一會預言自己會活百歲。印度教和密宗都推崇神通,但是因爲沒有正確知見和禪定,所以往往是用鬼神通、黑魔法,前言與後語互相矛盾衝突也是他們的常態。)》》

** ** 《《他曾對麥克勞德小姐說,源自 Belur Math(維韋卡南達的修道院/大學之一)的精神理想將影響世界思想潮流 1100 年… 保留維韋卡南達印度教品牌的吠檀多協會目前只有約 22,000 名會員,在世界各地設有十幾個中心。因此,它不太可能成為斯瓦米宏偉設想的「全球精神復興」的任何重要組成部分。那麼,維韋卡南達的實際遺產中最重要的部分,除了單純的組織公關之外,可能僅僅在於他為隨後一個世紀追隨他進入美國的其他東方教師鋪平了道路。 CHAPTER III

[Vivekananda] is seen not just as a patriot-prophet of resurgent India but much more—an incarnation of Shiva, Buddha and Jesus (Sil, 1997). BORN IN 1863 IN CALCUTTA, Vivekananda began meditating at age seven, and claimed to have first experienced samadhi when eight years old. He regarded himself as a brahmachari, a celibate student of the Hindu tradition, who worked hard, prized ascetic disciplines, held holy things in reverence, and enjoyed clean words, thoughts, and acts (Nikhilananda, 1996). was constantly flattered and petted by his frankly enchanted homoerotic mentor [i.e., Ramakrishna], fed adoringly by him, made to sing songs on a fairly regular basis for the Master’s mystical merriment, and told by the older man that he was a ... realized individual through his meditations ... [an] eternally realized person ... free from the lure of ... woman and wealth (Sil, 1997). Interestingly, in later years, Vivekananda actually claimed to be the reincarnation of Shankara (Sil, 1997). In any case, following a dozen years of increasing devotion to his dearly departed guru, Vivekananda came to America at age thirty. There, he represented Hinduism to American men and women at the 1893 Parliament of Religions, held in Chicago. A total stranger to the world of extroverted, educated, and affluent women, he was charmed by their generosity, kindness, and frankly unqualified admiration for and obsession with a handsome, young, witty, and somewhat enchantingly naïve virgin male from a distant land (Sil, 1997). he visited brothels and consumed alcoholic beverages in the company of his friends (Sil, 1997). So it was just a few drinks too many. In a whorehouse. Nothing unexpected from a savior “chosen by God as His instrument to help Him” in the salvation of humanity. Either way, though, “if you keep on playing with fire” you’re going to get burned, as Vivekananda himself observed: Once in me rose the feeling of lust. I got so disgusted with myself that I sat on a pot of burning tinders, and it took a long time for the wound to heal (in Sil, 1997). The enthusiastic young monk’s hopes of effecting global change, further, were not limited to a spiritual revolution, of “Hindus ‘round the world.” Rather, among his other vast dreams were those of a socially progressive, economically sovereign and politically stable India (Sil, 1997). The realization of those goals, however, was to come up against certain concrete realities not anticipated by the swami, including the need to think ahead in manifesting one’s ideas. Indeed, Vivekananda was, it seems, explicitly opposed to such an approach: Plans! Plans! That is why you Western people can never create a religion! If any of you ever did, it was only a few Catholic saints who had no plans. Religion was never, never preached by planners! (in Nikhilananda, 1996). I have roused a good many of our people, and that was all I wanted (in Nikhilananda, 1996). I have given up at present my plan for the education of the masses (in Sil, 1997). Swami had good ideas—plenty—but he carried nothing out .... He only talked (in Sil, 1997). The chain-smoking, diabetic sage, apparently “going gentle into that dark night,” nevertheless passed away only a few years later, in 1902, after years of declining health. Reaching only an unripe age of thirty-nine, he “thus fulfill[ed] his own prophecy: ‘I shall not live to be forty years old’” (Nikhilananda, 1996). Of course, there are prophecies, and then there are earlier prophecies: Vivekananda declared solemnly: “This time I will give hundred years to my body.... This time I have to perform many difficult tasks.... In this life I shall demonstrate my powers much more than I did in my past life” (Sil, 1997). The spiritual ideals emanating from the Belur Math [one of Vivekananda’s monasteries/universities], he once said to Miss MacLeod, would influence the thought-currents of the world for 1100 years.... |

| Home » » Swami瑜伽性侵大師 |

简体 | 正體 | EN | GE | FR | SP | BG | RUS | JP | VN 西藏密宗真相 首頁 | 訪客留言 | 用戶登錄 | 用户登出

- 評論南傳佛教上座部及印順法師

- 喇嘛教本質的海濤法師放生爭議

- 雙身法黃教祖師--宗喀巴(廣論)淫人妻女秘密大公開

- 淨空法師揭發邪惡之偽藏傳佛教開示輯

- 慧律法師破斥藏傳假佛教及「人間佛教」之邪說

- 淫人妻女之活佛喇嘛(偽藏傳佛教)性侵害事件秘密大公開

- 雙身法六字大明咒秘密大公開

- 十七世大寶法王噶瑪巴性醜聞

- 高僧學者名人批判雙身法之西藏密宗(偽藏傳佛教)證據大公開

- 藏密本質的聖輪法師性醜聞事件簿

- 雙身法達賴喇嘛秘密大公開

- 殘暴的偽藏傳佛教、西藏密宗、喇嘛教殺人證據

- 宗教性侵防治文宣教育(歡迎流通)

- 雙身法喇嘛教(西藏密宗、偽藏傳佛教)秘密大公開

- 雙身法紅教祖師--蓮花生(大圓滿)淫人妻女秘密大公開

- 雙身法白教祖師--密勒日巴(大手印)淫人妻女秘密大公開

- 真心新聞網、各家宗教新聞

- 漫畫-密宗活佛、喇嘛、仁波切

- 喇嘛教雙身法連載專欄:台灣玉教室

- 偽藏傳佛教雙身法分享專欄:-讀者來鴻

- 罪惡達賴 罪惡時輪

- 偽藏傳佛教(藏密)問答錄●學密基本常識

- Swami瑜伽性侵大師

- 人面獸心-索達吉堪布雙修大揭密

- 國學大師-南懷瑾雙修大揭密

- 卡盧仁波切雙修大揭密

- 索甲仁波切雙修大揭密

- 真佛宗盧勝彥雙修大揭密

- 破斥藏密多識喇嘛《破魔金剛箭雨論》之邪說

- 陳健民上師講述如何修學密宗邪淫男女雙修灌頂

- 剖析天鑒網悲智版主愚癡言論輯

- 嗜血啖肉的人間羅剎---喇嘛教絕非佛教

- 嗜食糞尿精血等穢物的藏傳佛教

- 附佛外道-法輪功的秘密

- 揭發「藏傳佛教」轉世活佛的騙人內幕

- 認識真正善知識-蕭平實老師

- 偽藏傳佛教詩詞賞析

- 第一部揭開西藏神秘面紗的大戲--西藏秘密

- 破斥遼寧海城大悲寺妙祥法師抵制正法

- 破斥一貫道

- 破斥瑯琊閣

佛教未傳入西藏之前,西藏當地已有民間信仰的“苯教”流傳,作法事供養鬼神、祈求降福之類,是西藏本有的民間信仰。

到了唐代藏王松贊干布引進所謂的“佛教”,也就是天竺密教時期的坦特羅佛教──左道密宗──成為西藏正式的國教;為了適應民情,把原有的“苯教”民間鬼神信仰融入藏傳“佛教”中,從此變質的藏傳“佛教”益發邪謬而不單只有左道密宗的雙身法,也就是男女雙修。由後來的阿底峽傳入西藏的“佛教”,雖未公然弘傳雙身法,但也一樣有暗中弘傳。

但是前弘期的蓮花生已正式把印度教性力派的“双身修法”帶進西藏,融入密教中公然弘傳,因此所謂的“藏傳佛教”已完全脱離佛教的法義,甚至最基本的佛教表相也都背離了,所以“藏傳佛教”正確的名稱應該是“喇嘛教”也就是──左道密宗融合了西藏民間信仰──已經不算是佛教了。